This post is inspired by Tomas Sedlacek’s excellent book Economics of Good and Evil. I have already posted several, for me at least, thought-provoking extracts from the book, and there are more to come. Here I want to discuss some of the issues which arise from considering how economics is impossible to separate from ethics, though many of its modern practitioners would think otherwise. Even if they do acknowledge this truth, the ethics of modern economics are generally unspoken or presupposed. They exist, but are not often considered open to debate, except by those inclined to more heterodox perspectives.

This post is inspired by Tomas Sedlacek’s excellent book Economics of Good and Evil. I have already posted several, for me at least, thought-provoking extracts from the book, and there are more to come. Here I want to discuss some of the issues which arise from considering how economics is impossible to separate from ethics, though many of its modern practitioners would think otherwise. Even if they do acknowledge this truth, the ethics of modern economics are generally unspoken or presupposed. They exist, but are not often considered open to debate, except by those inclined to more heterodox perspectives.

The goods

What is counted as good in modern economics? To start with, most policymakers prioritise GDP growth, or perhaps growth in productivity, given their role in driving material prosperity and creating jobs. Increasing quantities of goods and services produced by a growing economy are part of the result. But it is surely rather short-sighted to assign ‘good’ only to the material aspects of production. Some ecological economists argue that the priority given to continuous growth in economic output are so damaging to planetary ecosystems and resources that we should aim for something like zero growth, or even ‘degrowth’. From their perspective, continued increases in GDP are ultimately unsustainable, and a radically different kind of economy is the required response. Space should be made for the poorest countries to grow, but the richest should radically change tack.

In neoclassical microeconomics, and the ‘microfounded’ macroeconomics to which it gives rise, the goal of rational individuals is that of maximising utility. If economic agents are free to do so, this should produce the social good. But we cannot observe or measure utility, except by what economists call “revealed preference” in consumption. Individuals reveal what they value through their choices in the marketplace. All this is tempered by the presence of market imperfections which either calls for government intervention to correct the imperfections, or laissez-faire for those who believe that governments can only make things worse.

Straying into the world of ethics, Amartya Sen has argued that the “good” we should aim to achieve through economic development should be a kind of freedom enabled by what he calls capabilities, or a broad notion of human functioning. This requires increased material prosperity, but public goods such as education, healthcare, workers’ rights and satisfactory conditions in the workplace are also vital to human wellbeing, both at the individual and the social level.

These ideas suggest, in the spirit of heterodox thinking, that economics should be seen as far more than the science of rational choice, as many contend. Rather it remains a social science, with a reliance, either implicit or explicit, on ethics. There are ‘goods’ to be aimed for, which can include material and social prosperity, various kinds and degrees of equality, as well as forms of freedom, among others. These apply to the individual but also to the community and society.

The bads

What of the evil or ‘bads’ implied by our theories of economics? Following the above, we can argue that the lack of such goods needs to be overcome by our economic theories and policies. Inequality or injustice, poverty and instability could all be considered as targets for economists to help us overcome.

What else? Historically, economic ideas have become inextricably bound to notions of human progress. Some see a contest between nature and civilization. Humanity sprung from nature, but has worked hard to overcome its limitations. But I would argue that society is dependent upon nature. Even if we transform natural resources and the environment around us, this requires a degree of knowing in order to avoid destroying its foundations. Once again, this is an argument of ecological economics and sustainable development. Whether we perceive humanity as being separate from nature or one with it makes a big difference to the kind of economics we pursue and the future we create for ourselves and the planet.

Perhaps more abstractly, a certain amount of social chaos is seen as bad and order as good. Once again, this is a matter of degrees in both directions. Humanity seems to be able to create a certain amount of order out of what we perceive as chaotic, not least in our economic models and theories. Chaos and complexity theories, which have been applied in economics, suggest that subtle changes at the micro-level can produce major changes at the macro or social level. This requires a different kind of policymaking on the part of governments and their advisors.

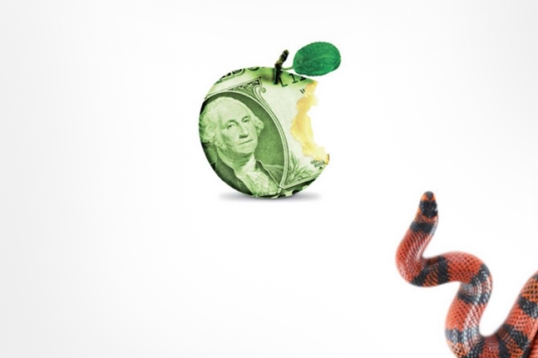

Money is sometimes considered as bad, or at least the excessive love of and attachment to it. It is desired for what it can buy, and perhaps the power it can wield. Taken to excess, this can become pathological, both for individuals and society, as Keynes argued long ago.

We can therefore see that the role of (economic) science is inextricably bound up with reducing evils or bads and increasing goods. But there should be a much greater role for ethical debate as to how these are defined.

The individual versus the social?

Good and evil can be defined at the individual but also the social level. According to various economic theories, in certain contexts they coincide, but in others they diverge, with a range of implications for economic theory and policy.

Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ holds that in a competitive marketplace, individuals pursuing their own self-interest will create an unintended social good. This will be in the form of increased material output as the market grows underpinned by an increased division of labour and specialisation in production. One of today’s classically-oriented economists, Anwar Shaikh, has argued that what he calls ‘real competition’ leads to turbulent fluctuations of profit rates around some normal level across industries when businessmen aim to maximise profits. Something similar happens to wage rates when workers also pursue such gain-seeking behaviour. For Shaikh, in the long run competition in a capitalist economy drives a search for cost reductions driven by investment in new technologies. It is this which drives economic growth.

Are these self-interested or gain-seeking behaviours ethical? Here there is scope for plenty of debate. Perhaps the search for personal wellbeing and prosperity is innate, or maybe it is to a degree shaped by society, or more satisfactorily, it is both. Capitalism is a relatively recent way of organising society, but it has surely been the most transformational, and the one that has driven much of humanity to undreamt of levels of wealth, technological sophistication and social dynamics and complexity. No-one planned it fully, rather these forms of progress have been cumulative and the historical outcomes of the decisions of billions of people.

Keynesian economics provides an example of how the coincidence of private and public goods and prosperity need not coincide in particular contexts. A household or firm which chooses not to, respectively, consume or invest in the presence of heightened uncertainty about the future, may be making a rational decision. If enough of them do so, this will constrain or reduce aggregate demand and lead the economy into stagnation or recession, with rising unemployment a likely result. What seems individually rational may turn out to be collectively irrational. This may require a response from the state to expand demand and mitigate the downturn. Those who preach that a prudent household will save, whereas a profligate one will consume all their income, may be right some of the time, and even right for individual households, but such considerations mean that appeals to prudence in the face of recessionary forces can produce collective social and economic bads or ‘evil’ in terms of reduced prosperity and employment.

Keynes argued that investment drives economic prosperity, but that entrepreneurs were motivated more by what he called “animal spirits” than by rationality. Waves of optimism and pessimism could drive the ups and downs of the economy as investment fluctuates. Animal spirits, or the emotional impulse to action or inaction might seem to be the antithesis of the rational individual in a science of choice. Some philosophical traditions which view intellectual thinking and rationality as good might see them as bad by themselves, even if they admit that without them the drive for prosperity would whither and die. But surely we are far more than our rational mind: just look at our politics, and our entertainment industry. Today’s wilier leaders know that most of us are driven more by emotion than by the good or bad of policy detail.

I do not think that the animal spirits of entrepreneurs are the sole foundation of economic growth and fluctuations. The idea leaves too much to subjective factors, even if they are part of it. Subjective decisions depend to a degree upon particular contexts, and thus have an objective component. The two come together in our society and its evolution, for good or for bad.

Economics as a solution?

Thus modern economics purports to provide solutions to various social ills, and in its narrow mainstream form, it neglects the study of ethics despite being implicitly founded upon it. Beyond the mainstream, solutions might range from the Keynesian wish to save capitalism from unemployment and perhaps extreme inequality and poverty, to the socialist wish to replace the system itself in order to eliminate all of its social evils, arguing that Keynesianism is doomed to fail. Those on the political right often advocate for increased economic freedoms, which some say is all that is needed to ensure sustained prosperity. Libertarians make a case for as minimal a state as possible. Such conceptions of freedom are necessarily rather narrow and tend to concentrate power in relatively few hands, and arguably limit the freedoms of the majority. There are broader notions of freedom, as Sen argues with his notion of capabilities underpinned by collective action, as much as simple appeals to negative freedom as opposed to its positive variant.

Gordon Gekko in the film Wall Street famously said that “greed, for lack of a better word, is good”. It is certainly a characteristic of our capitalist economy, that gain-seeking behaviour can produce social prosperity. Greed is such behaviour taken to its limit, and an account of where, despite social benefits, this leaves the individual morally and spiritually is beyond the realm of much of today’s economics. Such ethical limitations need to be exposed and opened up to debate, or else we are heading blind into the future. The ever quotable Keynes once said that:

“For at least another hundred years, we must pretend to ourselves and to every one that fair is foul and foul is fair; for foul is useful and fair is not. Avarice and usury and precaution must be our gods for a little longer still.”

This often seems to be the case. For economics, a genuine conscious escape from values and ethics is surely impossible. Where it rejects such notions, it is in denial. Of course, values do change historically, as society itself evolves. Economics tries to help us understand how this society and its economy, in much of the world, are or aspire to hurtle into the future faster than ever before, trying to make some order out of chaos where it is perceived to occur, trying (at times in deluded and damaging fashion) to master nature, trying to turn bad to good, and even changing what we understand by these notions. Economics does have power and influence, but it needs to be more open to understanding its origins in social and ethical theory if it is to better serve humanity and the nature from which we emerged and depend upon.